Moths on the move fixed with tiny trackers, followed by plane

Very little is known about the travels of trillions of insects that migrate across the globe every year, so scientists put tiny trackers on giant moths in Germany to follow their flight paths by plane

READING LEVEL: GREEN

Trillions of insects migrate across the globe each year, yet little is known about their journeys. So to look for clues, scientists in Germany took to the skies, placing tiny trackers on the backs of giant moths and following them by plane.

To the researchers’ surprise, the moths seemed to have a strong sense of where they were going. Even when the winds changed, the insects stayed on a straight course, the scientists reported in a new study published in the journal Science.

Their flight paths suggest these death’s-head hawkmoths have some complex navigation* skills, the authors said, challenging earlier ideas that insects are just wanderers.

“For many, many years, it was thought that insect migration* was mostly just dictated* by winds and they were blowing around,” said lead author Dr Myles Menz, now working in Australia as a James Cook University zoologist*.

It’s been tough for scientists to get a close look at how insects travel, in part because of their small size, Dr Menz said. The kinds of radio tags used to follow birds can be too heavy for smaller flying animals and insects.

But transmitters* have gotten tinier. And it helps that the death’s-head hawkmoth is huge compared to other insects, with a wingspan up to 127mm.

The iconic* species — dark coloured with yellow underwings and skull-like markings — was able to fly well with the tiny tracker glued to its back, said study co-author and Max Planck Institute for Animal Behavior migration researcher Dr Martin Wikelski.

The moths are thought to migrate thousands of kilometres between Europe and Africa in the autumn, flying by night.

For the study, researchers released tagged moths in Germany in the hopes they’d start flying on their migration path toward the Alps*.

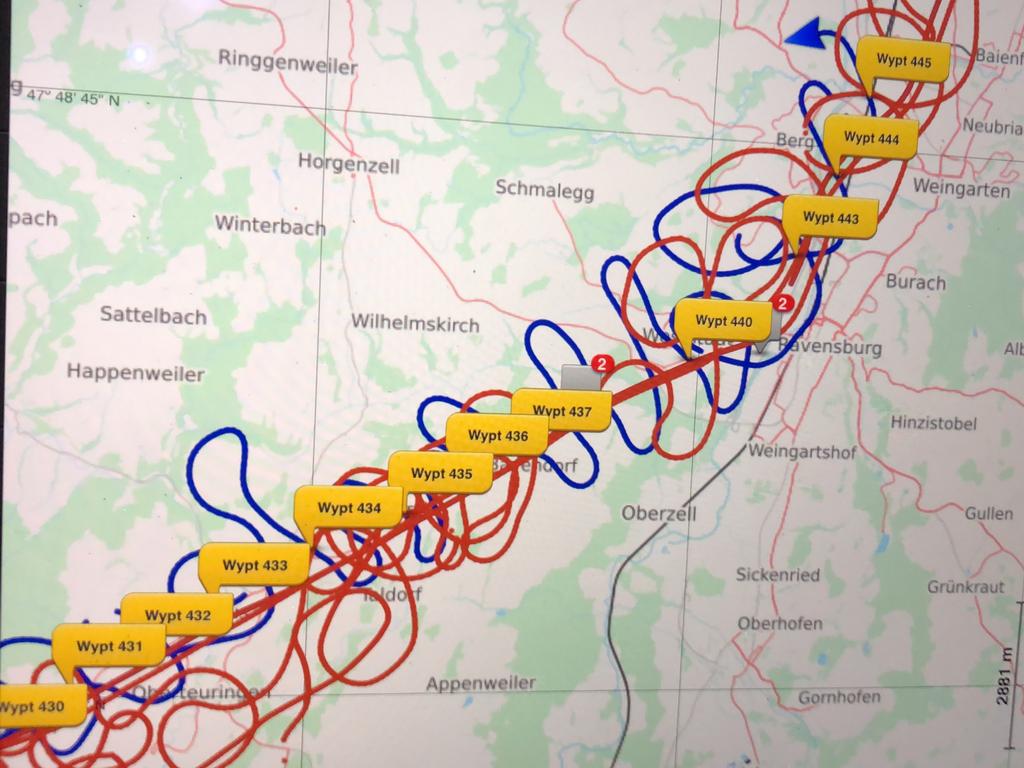

Dr Wikelski, the study’s pilot, took off in his plane, circling the area and waiting for any moths on the move. If he did pick up a signal from a tiny traveller, he would follow its radio blips for hours at a time.

“The little moth is guiding you,” he said.

The researchers followed the flight paths of 14 moths, with their longest track around 90km.

Not only did the moths fly in straight lines, but they also seemed to work around wind conditions, Dr Menz said, flying low to the ground when the winds were against them, or rising up to catch a helpful tail wind.

Though the number of moths tracked was fairly small, getting any close-up look at insect migration was significant, said University of Guelph Associate Professor Ryan Norris, an insect and bird migration researcher in Canada who was not involved in the study.

“I was surprised at how far they could track them,” Dr Norris said. “And it certainly is surprising that individual moths stay on this straight trajectory*.”

GLOSSARY

- navigation: deliberately setting course and moving from one place to another

- migration: seasonal movement of animals and insects from one place to another

- dictated: decided, influenced, determined by

- zoologist: scientist who specialises in the study of animals

- transmitter: apparatus for transmitting radio or television signals

- iconic: widely recognised, considered to represent something

- the Alps: large European mountain range from Austria and Slovenia in the east, through Italy, Switzerland, Germany and Liechtenstein, to France in the west

- trajectory: path taken by an animal or object as it flies or moves

EXTRA READING

Heaviest moth in the world found at primary school

Bees in ‘lockdown’ to stop parasite spread

Shark cam captures life and death struggles

QUICK QUIZ

- What is the wingspan of the death’s-head hawk moth?

- The moths are thought to migrate between which two continents?

- Where were the moths tagged and how did researchers follow their journey?

- How many moths were tracked in the study?

- The longest tracked journey was across what distance?

LISTEN TO THIS STORY

CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES

1. Tell the moth’s story

How do you think the moths felt about having the trackers on their backs and being studied? Rewrite the story from a death’s-head hawk moth’s point of view.

Time: allow 30 minutes to complete this activity

Curriculum Links: English; Science

2. Extension

“Tracking where moths fly is a waste of time and money and Dr Mentz should stop this study!”

Imagine that you are Dr Myles Mentz. What would you write in reply to this statement?

Time: allow 30 minutes to complete this activity

Curriculum Links: English; Science

VCOP ACTIVITY

To sum it up

After reading the article, use your comprehension skills to summarise in a maximum of three sentences what the article is about.

Think about:

What is the main topic or idea?

What is an important or interesting fact?

Who was involved (people or places)?

Use your VCOP skills to re-read your summary to make sure it is clear, specific and well punctuated.