Learn the history of Australian referendums ahead of the latest on October 14

PART 1: Australia is off to the polls for a referendum. Let’s learn more about how and why we have referendums and what they mean for the country

READING LEVEL: RED

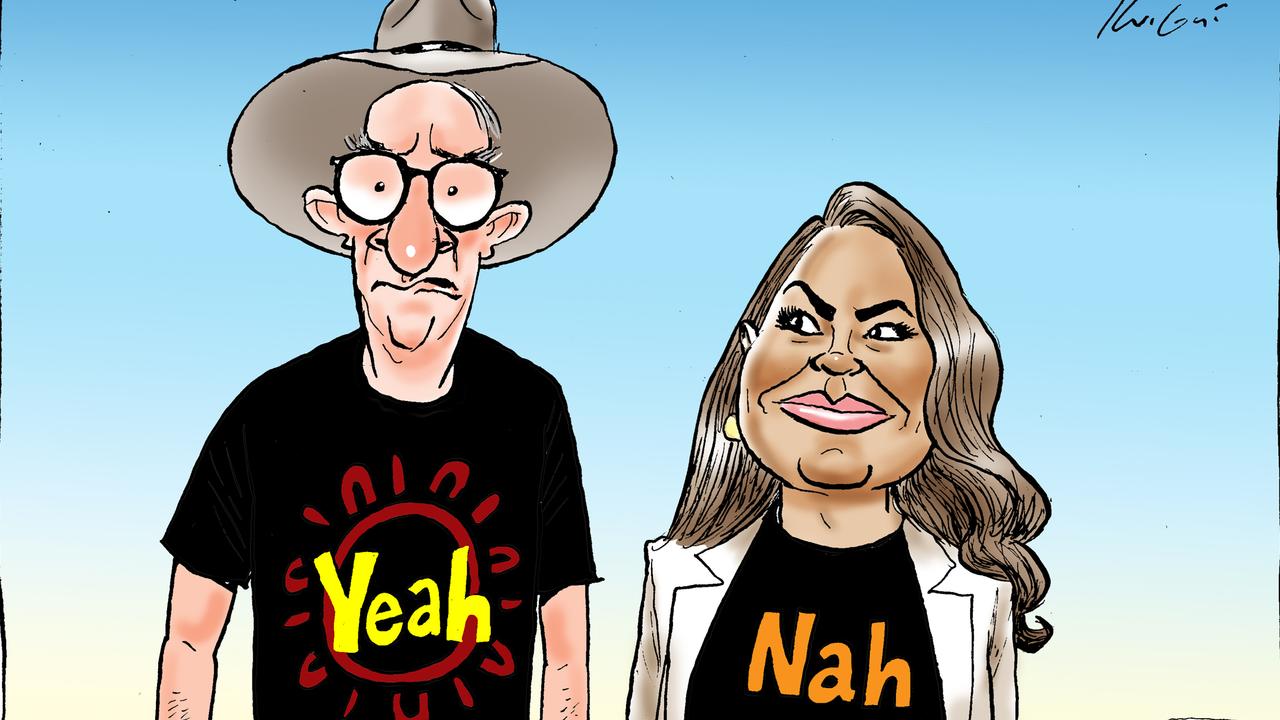

Before the October 14 referendum* on the proposed* Indigenous Voice to Parliament, it helps to understand how our system of government works.

Today in Part 1 of our series of Voice explainers, we look at why it’s hard to change the Australian Constitution.

WHAT IS A CONSTITUTION?

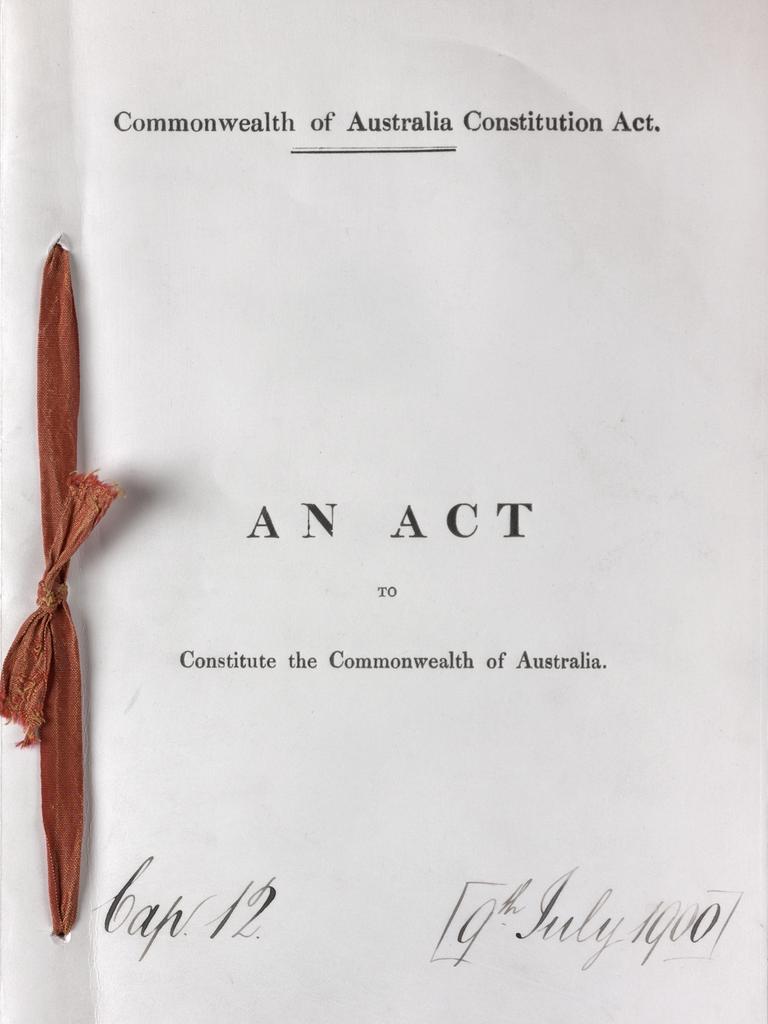

Constitutions are documents that set out the rules used to govern countries. Most nations have one, but some don’t. The UK and New Zealand have no one single document that sets out everything: they use a mix of different documents and traditions.

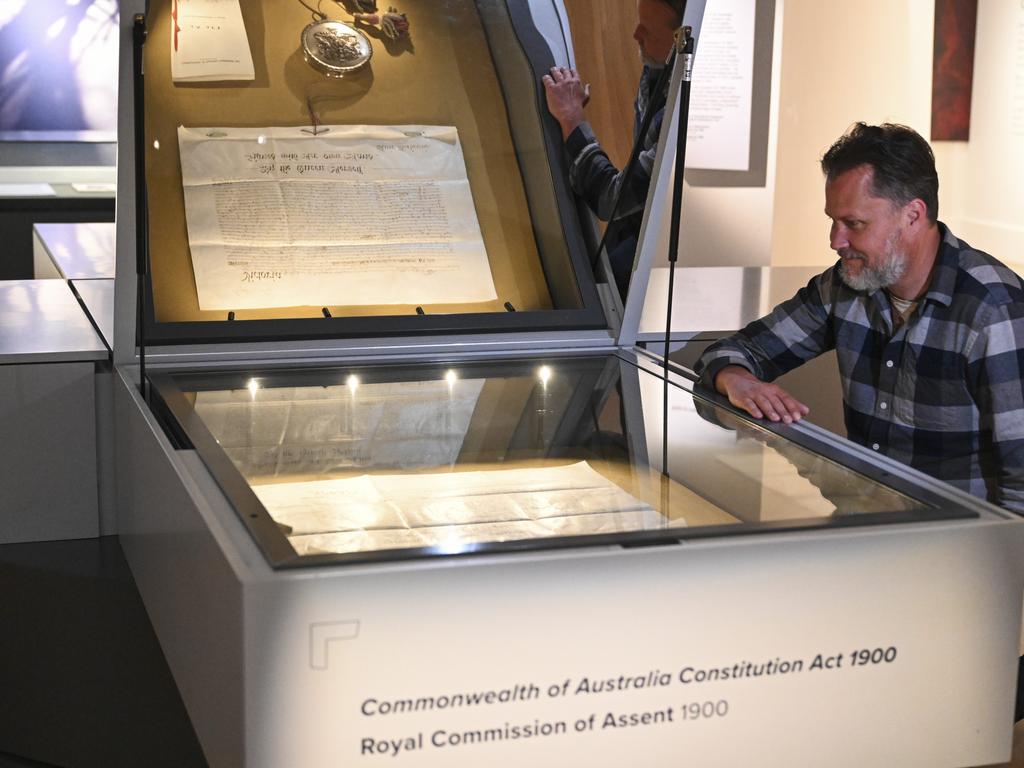

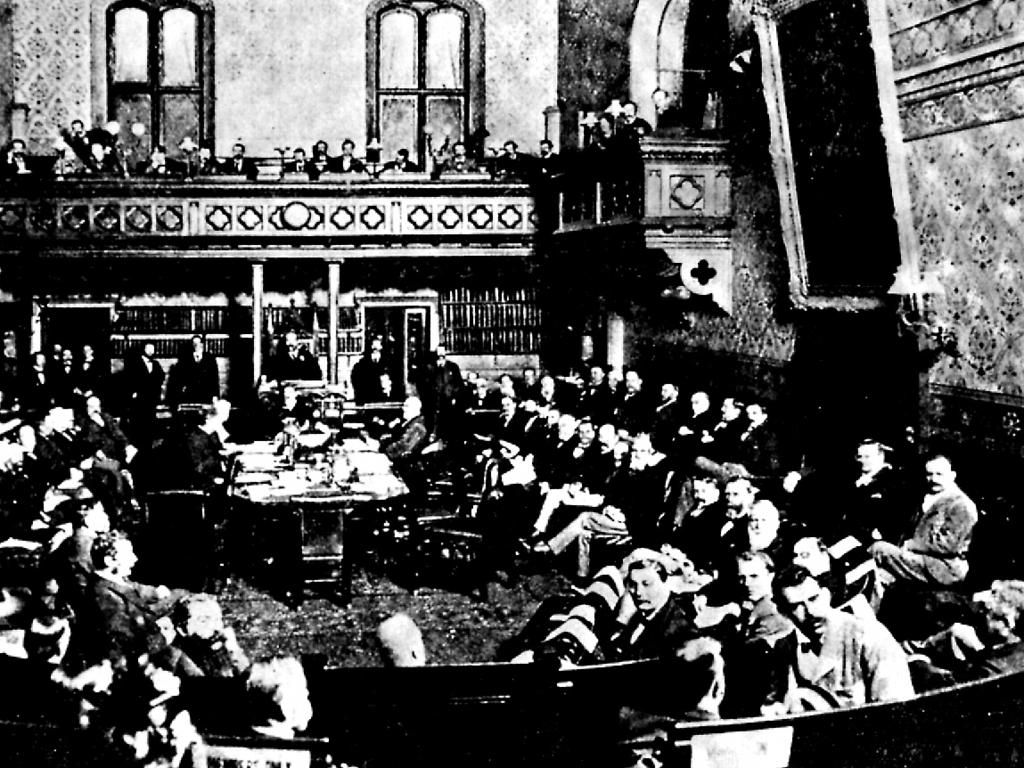

Australia’s Constitution was created in the late 19th century as the states and territories came together as a federation*. The Constitution and the country as one nation were born the same day – January 1, 1901.

The Australian Constitution has eight sections and 128 parts. It sets out how the country is run, with power split between an elected two-house federal parliament, six state governments, a High Court*, and a Governor-General* who represents the British monarchy*.

WHAT IS A REFERENDUM?

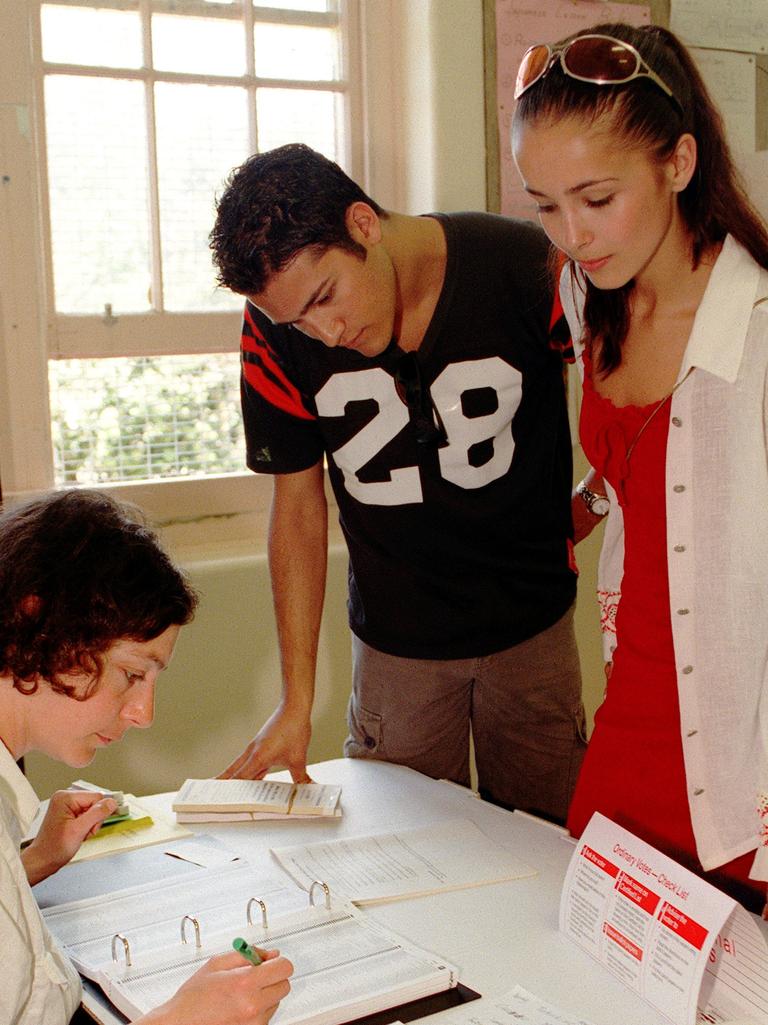

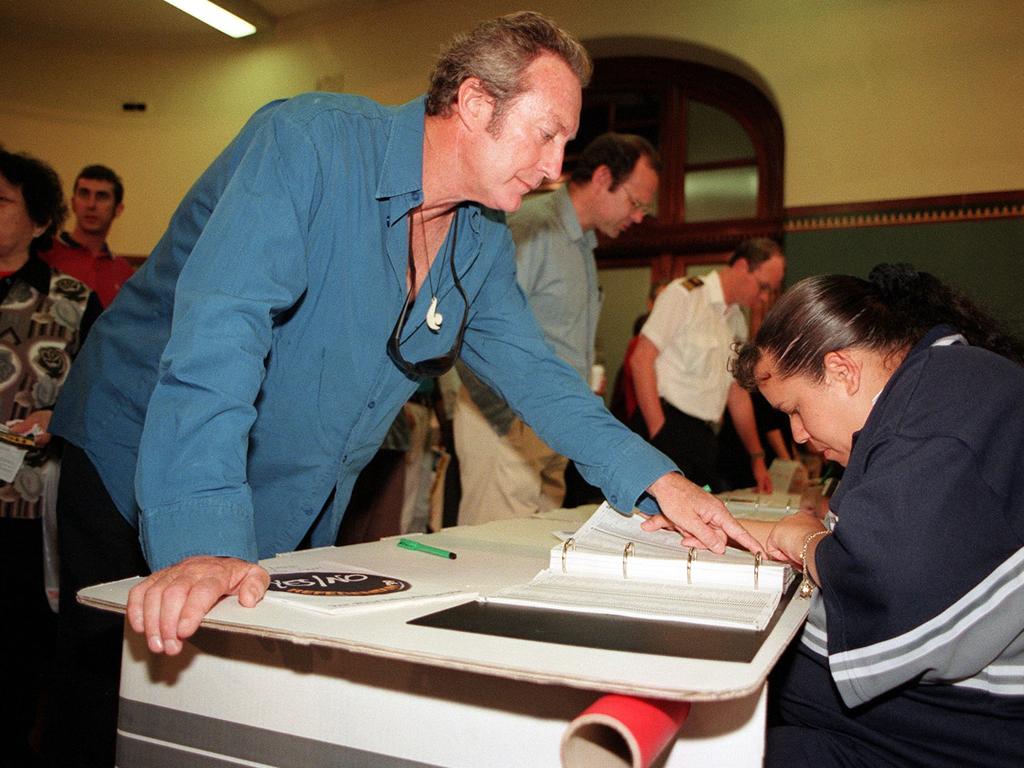

Members of parliament do not have the power to change the Constitution. Nor does the Governor-General. The Constitution says that only the people have that power, via a vote of all citizens on the electoral roll* – basically Australians aged 18 and over.

In total, 44 proposed changes to the Constitution have been put to the people since 1901.

It’s been 24 years since we last held a referendum. In 1999, Australians voted against becoming a republic* and adding a preamble* to the Constitution.

WHAT MAKES A REFERENDUM SUCCESSFUL?

Section 128 of the Constitution says that a double majority is needed for a constitutional referendum to succeed. A double majority means the majority of voters across the nation support the change and so do four of the six states.

It’s not an easy target to reach. Of the 44 referendum questions put to the Australian people since 1901, only eight have succeeded, and since 1984, all have failed.

Sydney University law expert Associate Professor Elisa Arcioni said the double majority was a deliberate design feature.

“(The) mechanism* (for success) was set up in the drafting of the Constitution to deliberately make it difficult to change the wording,” she said. “That was because the colonies* engaged in fierce negotiation and compromise* to create the national Constitution, and they wanted to retain* (their) power in that process of change.”

ARE THE RULES FOR SUCCESS FAIR?

Australia is admired for its free and fair elections, but there are quirks* in our system of government – and some seem to go against the democratic* ideal* that all votes should have the same value.

“Something that many people would be surprised to know is that the Constitution is not about formal equality; we actually have entrenched* inequalities,” said Assoc Prof Arcioni.

The Senate is a prime example.

While the states vary widely in the number of voters they have (from 400,000 in Tasmania to 5.5 million in NSW), the Constitution allocates* 12 senators to each.

Another inequality is how voters in the territories are counted in referendums.

Currently there are more than 315,000 people on the electoral roll in the ACT, and another 149,000 in the NT – but those combined 464,000 Australians have less of a say in the results of referendums than the voters in the states.

While their individual votes are counted as part of the national tally, they’re ignored completely in the “majority of states” calculation.

And if you think that’s unfair, consider that people who lived in the territories didn’t even get to vote in national referendums at all until after 1977, when they were given that right thanks to a successful referendum.

WHICH REFERENDUMS HAVE SUCCEEDED?

Australians have voted for diverse* constitutional reforms* since 1901:

– enabling elections to both Houses of Parliament to be held at the same time (1906);

– enabling the Commonwealth to take over state debts (1910);

– enabling reform to federal/state finances (1928);

– giving the Commonwealth power in the area of social services (1946);

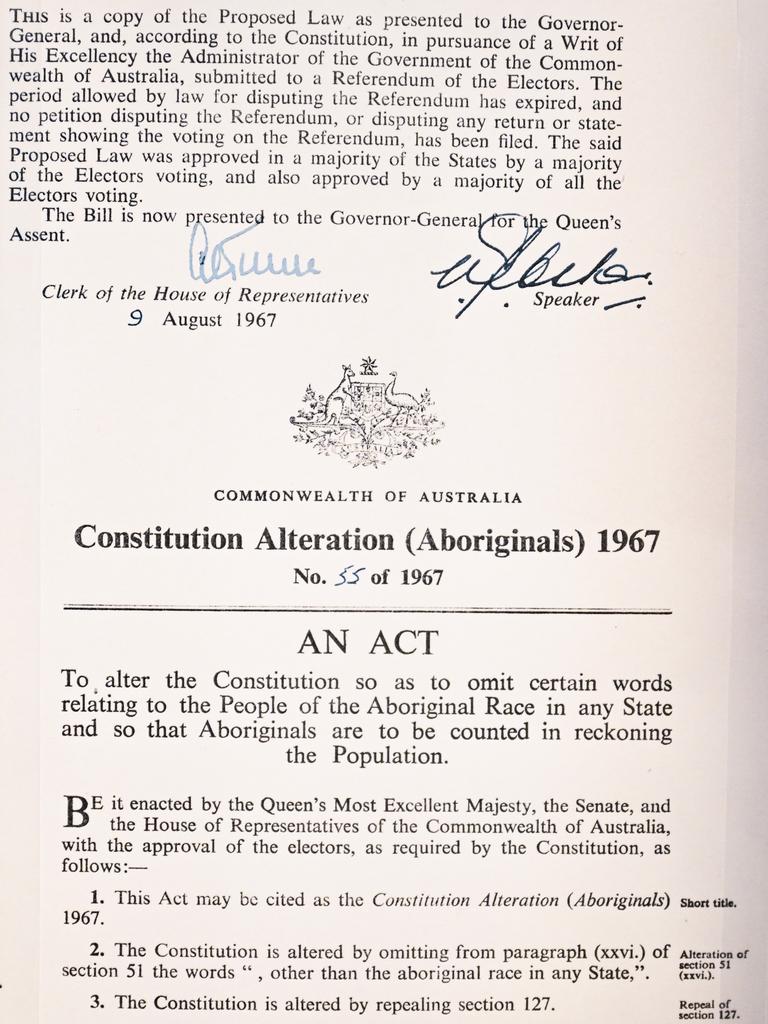

– giving the Commonwealth power to enact laws for Aboriginal people (1967);

– giving Territorians the vote in future referendums (1977);

– mandating* 70 as the retirement age for judges (1977);

– ensuring casual Senate vacancies are filled by a person of the same political party (1977).

Assoc Prof Arcioni said there’s little linking Australia’s eight successful referendums. Even the belief that all had bipartisan* support is open to debate.

“The variety of questions that have been put to referendums are really disparate*, so it’s hard to draw any particular pattern from the past,” she said.

HAVE MANY REFERENDUMS BEEN ABOUT INDIGENOUS ISSUES?

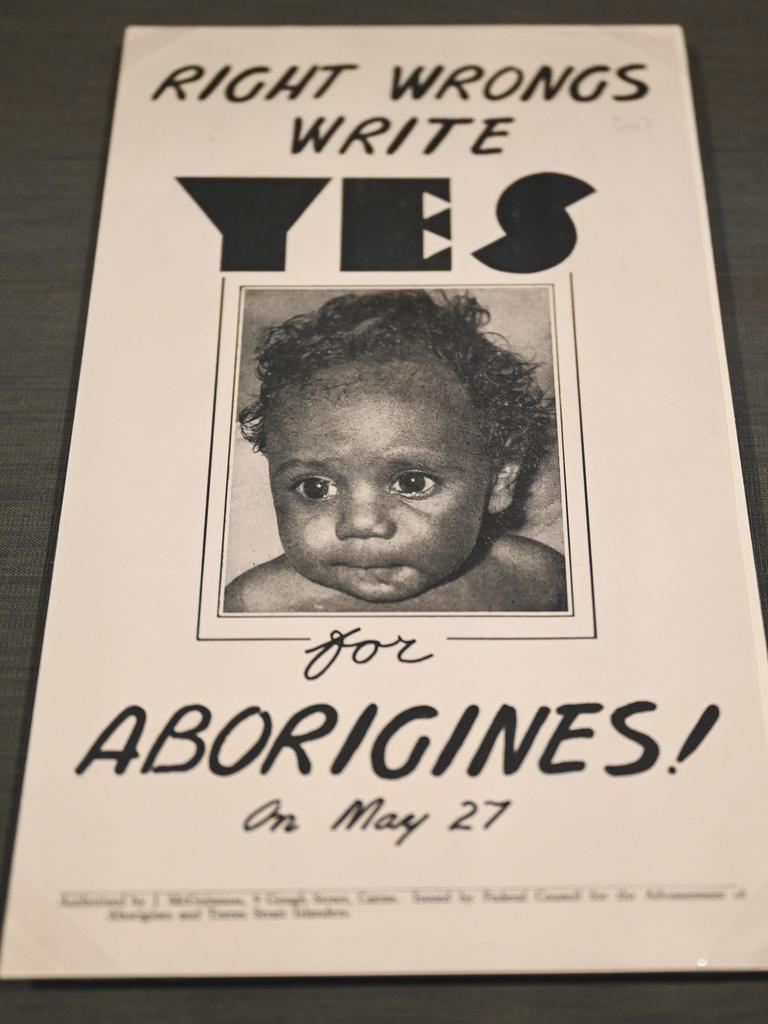

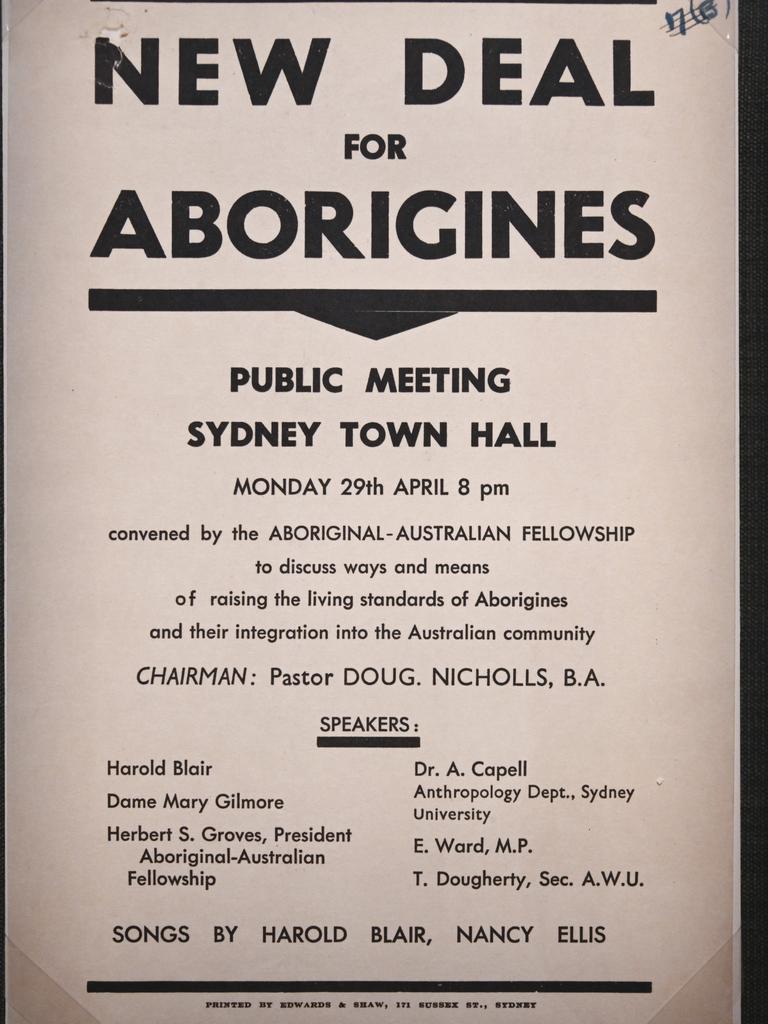

The 1967 proposal for the Commonwealth to enact laws for Aboriginal people was the most emphatically* supported referendum in Australia’s history. Almost 91 per cent of voters were in favour and the question was supported by all states.

But other referendums about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have failed.

An earlier version of the 1967 proposal was put to the people in 1944, as one of 14 areas of law where the Commonwealth wanted more power, but the yes vote did not reach a majority in either the popular vote or the majority of states.

The 1999 proposal for a Constitutional preamble would have included a statement recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, but more than 60 per cent of voters were opposed.

Please note this is an explainer series - curriculum-aligned classroom activities written by our teachers appear below; there is no separate workbook as in a Kids News Education Kit.

POLL

GLOSSARY

- referendum: when all eligible people in a country are asked to vote on a particular issue

- proposed: suggested, put forward a plan for consideration by others

- amend: change, alter, adjust, revise, make minor changes to improve, extend or reduce something

- federation: a group of independent states that come together under a central authority

- High Court: the highest court in the Australian judicial system

- Governor-General: the King’s representative in Australia, whose powers granted by the Constitution give them an important role maintaining its rules

- monarchy: a country with a king or queen, a political system based on the undivided rule of a single person

- electoral roll: a list of names and addresses of every registered, eligible voter

- republic: a government with a chief of state who is not a monarch and is usually a president

- preamble: introductory statement that comes before and leads to something else

- mechanism: a piece in a larger whole that helps something work better, a working part

- colonies: a country or area controlled politically by a more powerful country that is often far away

- compromise: a way of reaching agreement by each side giving up something it wants

- retain: keep, continue to have something

- quirks: different, interesting or unexpected features of a person or thing

- democratic: principles that allow everyone to be treated equally and have a say in decisions

- ideal: a principle that sets a high standard for behaviour

- entrenched: long established, deeply held, unlikely to change

- allocates: gives, accords or assigns a share of the total amount

- diverse: has a great deal of variety

- reforms: changes or improvements to laws and systems

- mandating: officially authorising and deciding something

- bipartisan: includes both major political parties

- disparate: very different, distinct, not the same in any way

- emphatically: strongly, enthusiastically, without doubt, forcefully

EXTRA READING

Uluru becomes Albo’s Mt Everest

Barbados breaks from Britain and becomes republic

QUICK QUIZ

- What are constitutions?

- On what date did Australia’s constitution and nationhood begin?

- What is a double majority?

- What are two ways in which votes in Australia are not of equal value?

- How many referendums have been put to the Australian people since 1901 and how many have succeeded?

LISTEN TO THIS STORY

CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES

1. What’s most important?

Create an information sheet for kids. The topic of your information sheet is what you think is the most important information in the story. You are not allowed to use words.

Time: allow at least 30 minutes to complete this activity

Curriculum Links: English, Visual Communication Design, Civics and Citizenship

2. Extension

What changes would you make to our existing Constitution to make it more fair or equal? For each change, write sentences explaining why you chose it and how you would change it.

Time: allow at least 25 minutes to complete this activity

Curriculum Links: English, Civics and Citizenship

VCOP ACTIVITY

Wow word recycle

There are plenty of wow words (ambitious pieces of vocabulary) being used in the article. Some are in the glossary, but there might be extra ones from the article that you think are exceptional as well.

Identify all the words in the article that you think are not common words, and particularly good choices for the writer to have chosen.

Select three words you have highlighted to recycle into your own sentences.

If any of the words you identified are not in the glossary, write up your own glossary for them.

Extension

Find a bland sentence from the article to up-level. Can you add more detail and description? Can you replace any base words with more specific synonyms?

Down-level for a younger audience. Find a sentence in the article that is high level. Now rewrite it for a younger audience so they can understand the words without using the glossary.