Elections Part 8: Understanding the role of the governor-general and the republic debate

PART 8: Learn about the role of the governnor-general – including why the prime minister must visit before an election – and what happens if we become a republic

READING LEVEL: GREEN

Australians watch for one big clue the prime minister is about to announce the date for an election. The clue? The prime minister visits the governor-general.

This is not a social catch up, it’s a requirement of the Australian Constitution, the set of laws for governing the country.

Once they have met and agreed on an election date, the governor-general issues the legal documents, called writs, necessary for an election.

Writs create vacancies for the politicians’ jobs in parliament, including the job of prime minister.

This is called dissolving parliament. The election’s purpose is to fill the jobs again with re-elected or newly elected parliamentarians*.

MEET THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL

The governor-general is the King’s representative in Australia.

Officially, the King is Australia’s head of state. In practical terms, the King appoints the governor-general and then the governor-general performs the duties of the head of state, usually for five years. The prime minister advises the King on who to appoint as governor-general.

The role of governor-general is a paid job and comes with the use of two residences, called Government House, in Canberra, and Admiralty House, in Sydney.

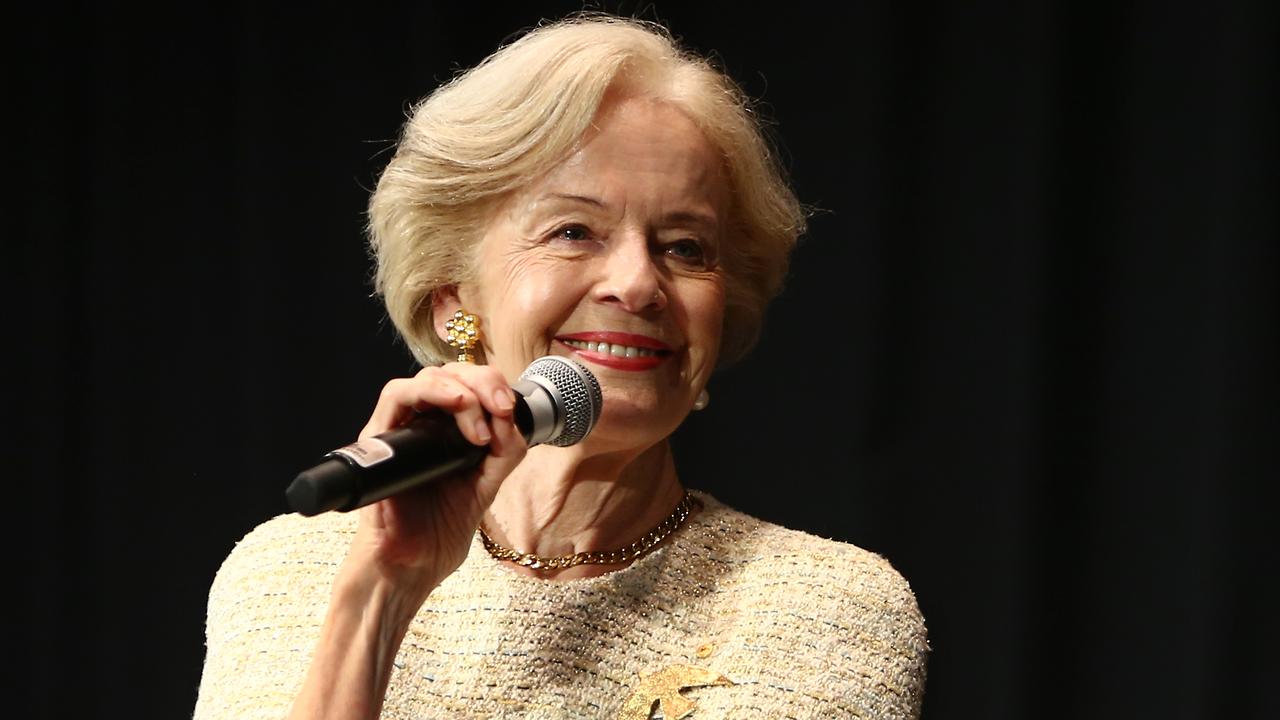

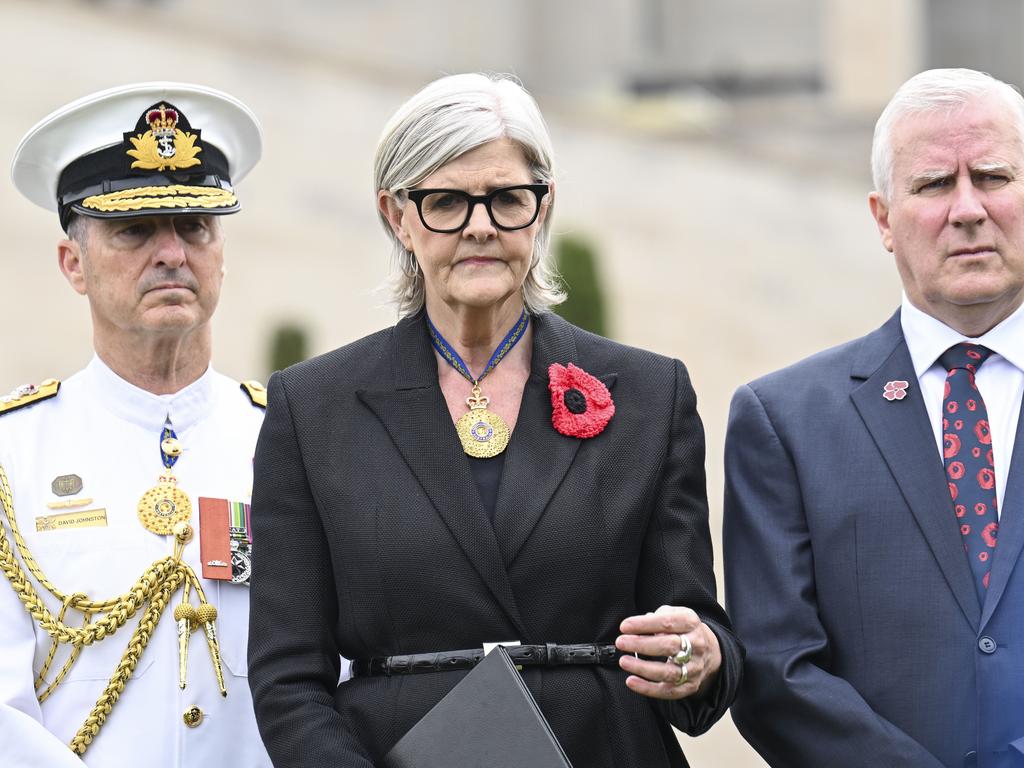

Community leader and businesswoman Sam Mostyn became Australia’s 28th governor-general on July 1, 2024. At the state government level, the governor is the role closest to the federal appointment of the governor-general.

FAMOUS NAMES

Australia’s first governor-general was John Hope, the seventh Earl of Hopetoun in Scotland. He was appointed in 1901 when Australia became a nation after Federation.

Australia didn’t have an Australian-born governor-general until 1931, when Sir Isaac Isaacs was appointed.

Dame Quentin Bryce was Australia’s first female governor-general, serving from 2008 to 2014. Ms Bryce is a lawyer and community and human rights advocate*.

THE JOB

The governor-general has three types of duties: ceremonial; Commander-in Chief of the Australian Defence Force; and constitutional.

CEREMONIAL duties include community work to support outstanding efforts by individual Australians plus charity, community, sporting and scientific research organisations. As a patron* of these organisations, the governor-general goes to events, gives speeches and helps spread the word about the good work being done.

The governor-general also hosts heads of state and other important visitors to Australia.

As COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF of the Australian Defence Force, the governor-general commissions* officers of the army, navy and air force, presents awards and attends services such as Anzac Day ceremonies.

CONSTITUTIONAL duties include issuing writs to dissolve parliament, in preparation for an election and then, after an election, commissioning* the newly elected prime minister, appointing ministers and swearing in* officials to other roles in parliament.

The governor-general also holds reserve powers. This means that when there’s a crisis in federal parliament, the governor-general can, in theory, step in and sort things out, like a chief umpire. An example would be appointing or dismissing a prime minister. In reality, the Australian Constitution isn’t all that clear on exactly what reserve powers are and how they can be carried out.

THE DISMISSAL

One of the most important moments in Australia’s political history happened on November 11, 1975, when the governor-general dismissed the Labor government, effectively sacking the prime minister.

The dismissal came after three years of political crises. Labor, led by prime minister Gough Whitlam, didn’t have a majority in the Senate*, which is like being in a sports team with fewer players than the other team. The government couldn’t get enough votes in parliament to pass new laws or approval to spend money. Eventually, the opposition* demanded the prime minister call an election, but he refused.

Governor-general Sir John Kerr, using reserve powers, sacked the prime minister for refusing to resign or call an election and then commissioned opposition leader Malcolm Fraser to be the caretaker* prime minister until the next election, which Malcolm Fraser’s coalition* won.

THE REPUBLIC DEBATE

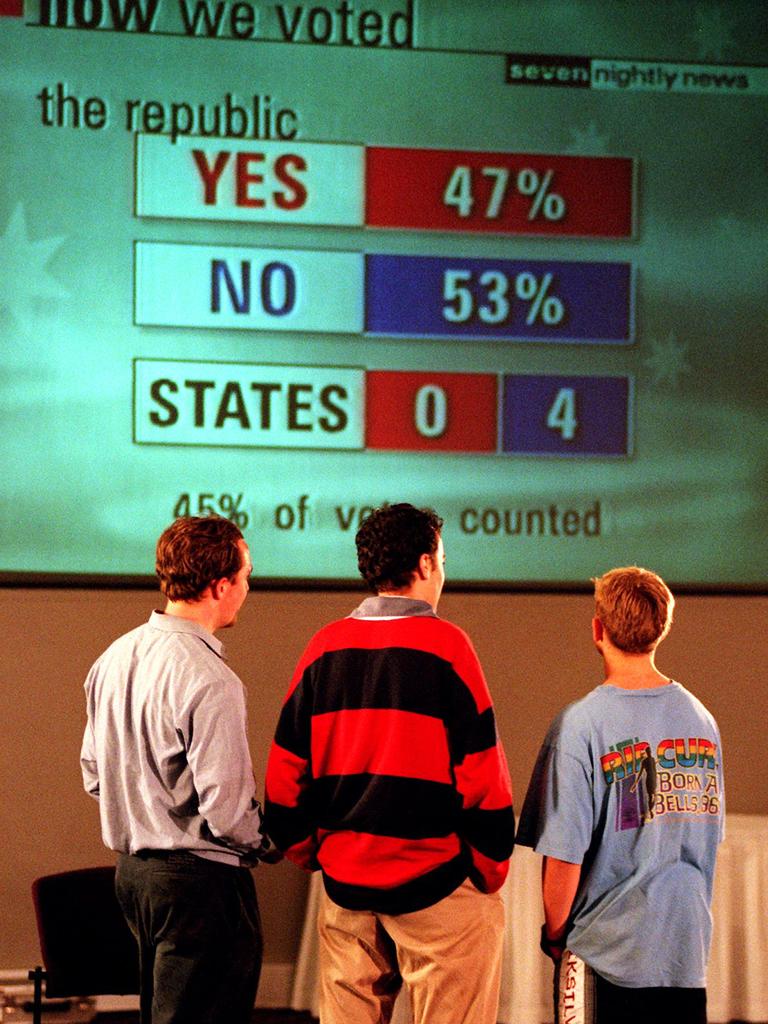

In 1999, Australians voted in a referendum to say whether they wanted to change the Constitution to become a republic, with a president appointed by parliament.

A referendum is a yes or no answer to a question for all Australians eligible to vote.

The 1999 referendum did not pass and Australia remained a constitutional monarchy, which means Australia kept the Queen as head of state, with the governor-general as her representative. Our head of state is currently King Charles III.

Despite the 1999 result, debate continues.

The main argument of republicans* is that Australians should decide who becomes our head of state on merit, rather than the position automatically being given to a foreign royal.

Monarchists* argue that a constitutional monarchy has worked well for the stability of Australian democracy so far.

Researchers often conduct surveys to understand Australians’ opinion on the topic. The survey results depend on how the question is asked and who is surveyed, but mostly, the majority of people surveyed say they want change, with slightly fewer not wanting change. In many surveys, lots of people say they are undecided.

Regardless of what surveys indicate, the only way for Australia to become a republic is to change the Constitution, and the only way to do that is with a referendum.

Referendums don’t have a history of success in Australia, whatever the topic. Since 1901 there have been 45 referendums, only eight of which resulted in change.

Sources:

gg.gov.au

aph.gov.au

naa.gov.au

republic.org.au

norepublic.com.au

GLOSSARY

- parliamentarians: members of parliament

- advocate: person who publicly supports a cause

- patron: person who gives financial or other support to an organisation

- commissions: formally authorises someone to do a job

- commissioning: formally authorising someone

- swearing in: administering a legal oath or commitment to a job

- Senate: upper house of parliament; checks on the work of the government

- Opposition: the major party in parliament that is not the government

- caretaker: someone who temporarily performs the duties of a particular official

- coalition: the Liberal/National party working together

- republicans: people who support a country being a republic

- monarchists: people who support a country keeping a royal head of state

EXTRA READING

Step inside the houses of federal parliament

Australia’s system of government

QUICK QUIZ

- Why does the prime minister have to visit the governor-general before calling an election?

- Who does the governor-general represent?

- Who is Australia’s current governor-general?

- What year did Australians vote in a referendum on the republic?

- How many referendums have been held in Australia and how many of these have resulted in a change to the Constitution?

LISTEN TO THIS STORY

CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES

Refer to the accompanying Elections Education Kit classroom workbook with 20 activities. It’s FREE when teachers subscribe to the Kids News newsletter.