Ancient Egyptian skulls show signs of surgery and cancer

A new study has shown Ancient Egyptians may have performed surgery to treat cancer as far back as 4000 years ago after hi-tech equipment detected cut marks in an ancient skull

READING LEVEL: ORANGE

A remarkable discovery has changed the way scientists think about the history of cancer treatment.

While many people mistakenly think of cancer as a disease that only affects modern-day humans, cancer has been around for thousands of years – and new research shows that humans have also tried to manage it for millennia*.

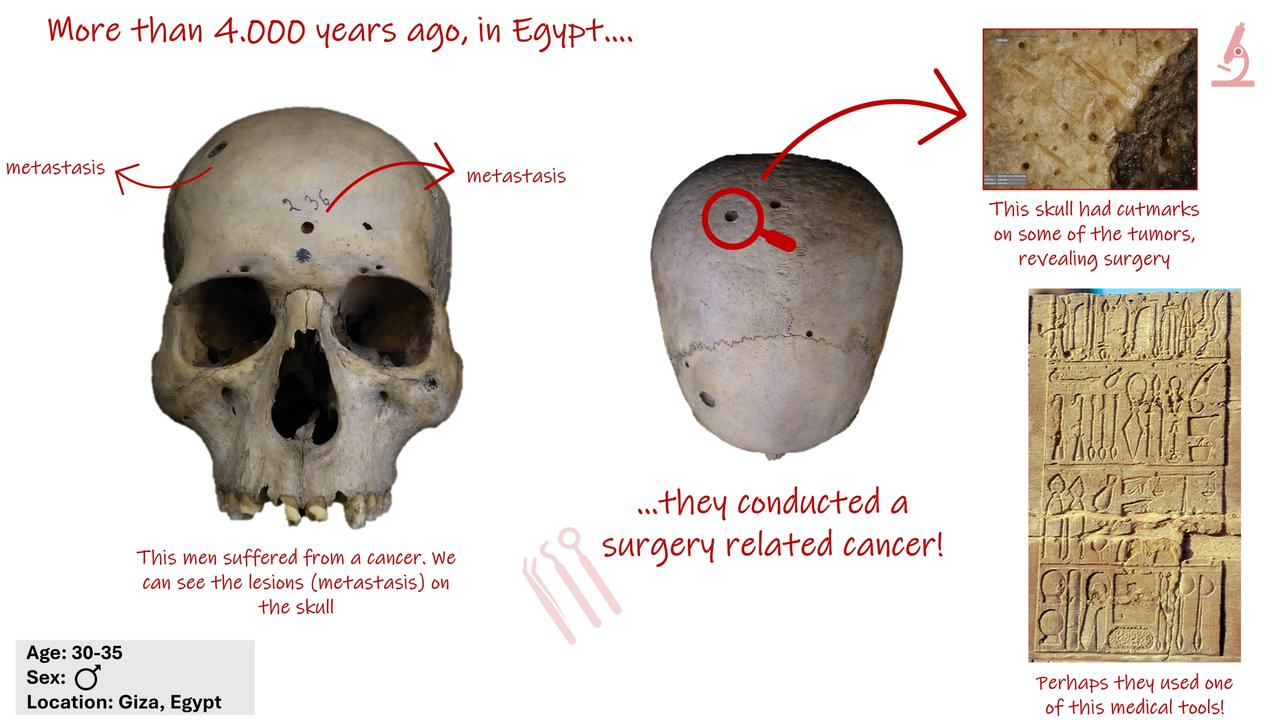

The study of two ancient Egyptian skulls held at the University of Cambridge in England has suggested that ancient Egyptians may have performed surgery in order to manage cancer.

Professor Edgard Camaros from the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain and his team of researchers were stunned when they found cut marks and evidence of cancer in the skulls of two ancient Egyptians that dated up to 4000 years old.

While Egyptians were known for having excellent medical knowledge and treating a range of diseases and injuries, including dental fillings, they had never been known to treat cancer.

Prof Camaros, along with researcher and co-author in the study, Dr Tatiana Tondini from the University of Tubingen in Germany, requested permission to study the two ancient skulls held in the Duckworth Collection of anthropological* artefacts at Cambridge.

Dr Tondini told Kids News that there were very few specimens that allowed for the study of ancient cancer (just 270 worldwide), since ancient people usually passed away before cancer affected their bones.

“We didn’t want to miss the opportunity to study such rare pieces,” she said.

The skulls had already been studied in 1963 by the palaeopathologist* Calvin Wells, however, the technology at the time wasn’t advanced enough to pick up the cut marks of surgery found on one of the skulls, she said.

“It was thanks to a HIROZ Digital Microscope HR-2016 that we spotted surgical cut marks around two secondary cancer lesions*,” she said.

In addition to the team’s powerful microscope, micro-CT scans enabled the scientists to identify 30 cancer lesions on the inside of the skull that had undergone surgery, which had belonged to a 30-35-year-old man who lived between 2687 and 2345BC.

The other skull, which belonged to a woman in her 50s who lived sometime between 663 and 343BC, had a large lesion thought to be from a cancerous tumour that destroyed the bone.

The researchers found two healed lesions that had been caused by traumatic injury from a sharp object that they believe could be signs of surgery.

The technology allowed the researchers to identify that the woman had suffered from osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer.

The researchers said they would now look to study the occurrence of cancer in other ancient cultures around the world.

While they would like to study cancer in the oldest surviving culture in the world, Indigenous Australians, they may be limited by the number of artefacts available.

“Indigenous Australians are unique in their history and have relatively little contact with other people until premodern history (compared to Eurasian and African people), which means that their genes (and their diseases) may not have changed much throughout thousands of years,” Dr Tondini told Kids News. “Studying ancient remains of Indigenous Australians could give invaluable insights into the evolution of several diseases, not only cancer.

“One limitation regarding cancer is that there are only two confirmed cancer cases on ancient human remains in Australia.”

Palaeopathology, the study of disease found in animal and human remains, aims to find out as much as possible about diseases in the past in order to help our understanding of diseases in the current day, Dr Tondini said.

“Our discipline is limited by the samples we work with, which depends on the funeral culture of some people, as well as the environment in which they were preserved,” she said. “Egypt is a great place thanks to its advanced funerary practices (think of mummification for instance) and to the dry weather, which preserves remains better.

“I am not particularly familiar with Australian paleopathology and osteoarcheology*, but I imagine there are almost ideal conditions for the preservation of ancient human remains.”

POLL

GLOSSARY

- millennia: thousands of years

- anthropological: relating to the study of humankind

- palaeopathologist: a branch of science that looks at the pathology of ancient human and animal remains, including the diseases present

- lesions: areas of damaged or abnormal tissue caused by injury, infection or disease

- osteoarcheology: the scientific study of human skeletons unearthed from archaeological sites

EXTRA READING

Kids’ drawings found in Pompeii

Spears returned after 254 years

Lush ancient Oz had giant koalas

QUICK QUIZ

1. How old are the skulls that were studied?

2. How many specimens across the world allow for the study of ancient cancer?

3. What two pieces of equipment helped the researchers identify signs of cancer and surgery?

4. Why would it be challenging to study cancer in ancient Indigenous Australians?

5. What two factors makes Egypt a good place to study ancient cancer?

LISTEN TO THIS STORY

CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES

1. Word study

Delve deeper into the meaning of the word paleopathology, taken from the text.

Find out the meanings of the Ancient Greek root words:

- palaios (paleo)

- pathos (path)

- logia (ology)

Brainstorm or research to find other words that also use these root words.

Time: allow 15 minutes to complete this activity

Curriculum Links: English

2. Extension

Repeat the above process for the word osteoarcheology.

Root words:

- osteon (osteo)

- archaia (arche)

- logia (ology)

Time: allow 15 minutes to complete this activity

Curriculum Links: English

VCOP ACTIVITY

BAB it!

Show you have read and understood the article by writing three sentences using the connectives “because’’, “and”, and “but” (BAB). Your sentences can share different facts or opinions, or the same ones but written about in different ways.