How Australia played an unexpected vital role in the moon landing broadcast

Australia played an unexpected important role in the moon landing by broadcasting the historic moonwalk to more than 650 million people across the world

READING LEVEL: GREEN

Australia played an unexpected important role in the moon landing by broadcasting* the historic moonwalk to the entire world.

The TV coverage was watched by an estimated 650 million people — about one-fifth of every person on Earth, becoming the world’s largest television audience in history at that time.

To cover the landing, NASA planned to use a telescope at Goldstone in California as the main signal receiver,* with Australian telescopes at Parkes and Honeysuckle Creek near Canberra to be backups.

But when Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin told mission control they were too excited to sleep and wanted to start their moonwalk early, Australia’s two telescopes became the main points of communication and would both take the first broadcast.

Australian Bryan Sullivan was working as a technician* in the control room at Honeysuckle Creek as they waited to hear from mission control if they would allow Armstrong and Aldrin to walk early.

Sullivan wrote a book about the experience with author Jackie French, called To The Moon And Back. Here is how he remembers taking part in one of the greatest moments in history.

****

Suddenly we heard the voice of CaPCOM — the capsule communicator from mission control — speaking to the astronauts: “Tranquillity Base, Houston. We thought about it. We will support it. We’re GO at that time. Over.”

Then we heard Neil Armstrong reply: ‘Roger*’.

Honeysuckle Creek was suddenly in the hot seat! We were the prime station for the most historic event of the century, now scheduled for around noon local time — in three hours’ time!

We felt as if a jolt of electricity had flashed through the entire station — but with station readiness tests still to be completed we had no time to talk about it, or to ring our families and friends.

Voice traffic with mission control intensified through our headsets, teleprinters* chattered away non-stop, the station’s TV monitors were connected to the Apollo video-processing equipment and the public relations officer alerted the VIPs (very important people) to get up to Honeysuckle Creek fast, so they wouldn’t miss anything.

At last we heard the calm voice from Goddard Operations on NET 2 say: ‘Honeysuckle, Network, that completes interface* testing, your site is GO! Standby for Houston.’

In the control room, Mike Dinn was ready with the final station status report ..... “Network, Honeysuckle, our status* is GREEN!’

We were ready.

The minutes ticked down … 3 minutes … 2 minutes … 1 minute …

Then at 11.15am the moon rose behind the gum trees.

Zero!

Immediately Honeysuckle Creek’s receivers locked onto the Eagle’s signals.

It was the moment we had worked towards for three years — and suddenly we had little to do.

Everything happened automatically now, as Honeysuckle Creek’s data* rippled through the complexity* of electronic systems and all the way across the world to the console* screens at mission control.

Far above us, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin started to check their life-support equipment — and our smug* calmness quickly changed to confusion!

Those blasted astronauts were not doing things according to the order on the flight plan!

The team at Honeysuckle Creek frantically* tried to keep up with what the astronauts were doing as the minutes dragged by.

The life support checks that the astronauts had to do before going out should have taken two hours. Today they were taking three hours.

Finally the checks were completed. We listened as the astronauts began to struggle into their spacesuits and life-support backpacks.

The TV screens were still blank — there could be no visual picture until Neil Armstrong switched on the camera mounted outside the landing craft when he came out of the hatch.

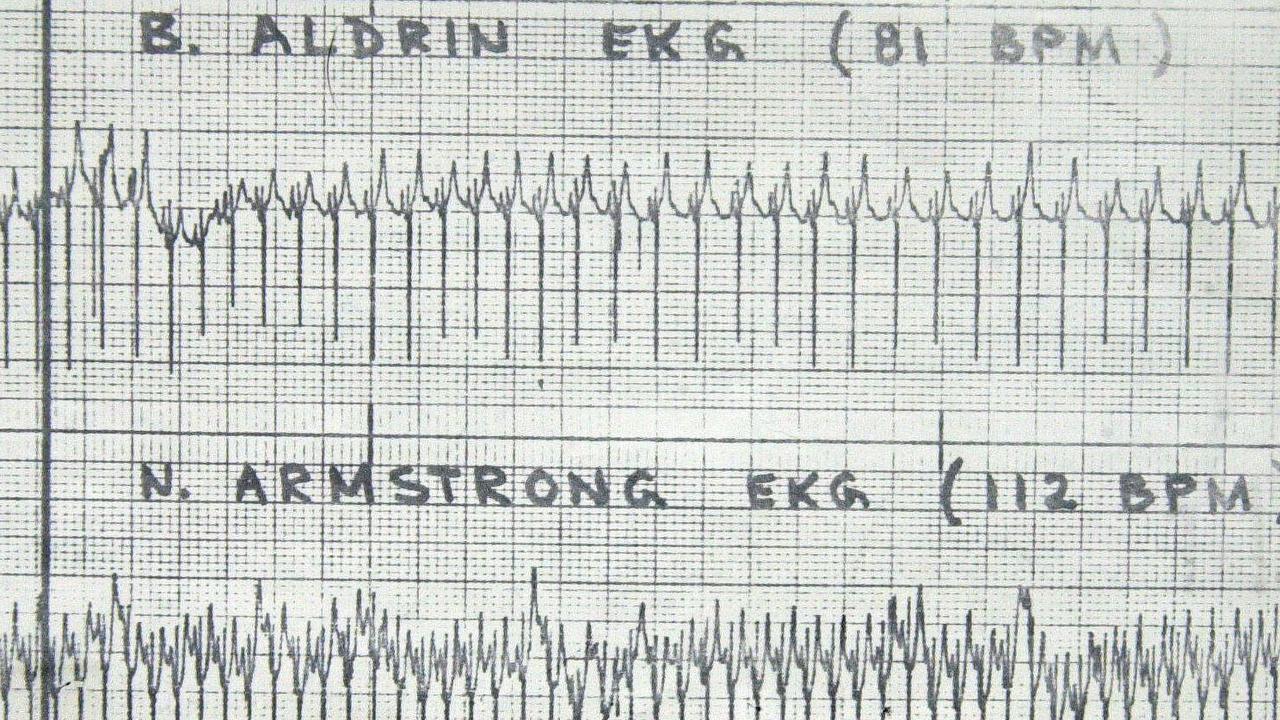

Honeysuckle Creek transmitted the final essential* information to mission control — biomedical data, to check that the astronauts were still strong and healthy.

At mission time, we heard Buzz Aldrin say to Neil Armstrong, ‘Okay. About ready to go down and get some moon rock?’

He handed Neil Armstrong a bag of rubbish to leave on the moon — this would lighten the load, saving on fuel for the return journey to the command module.

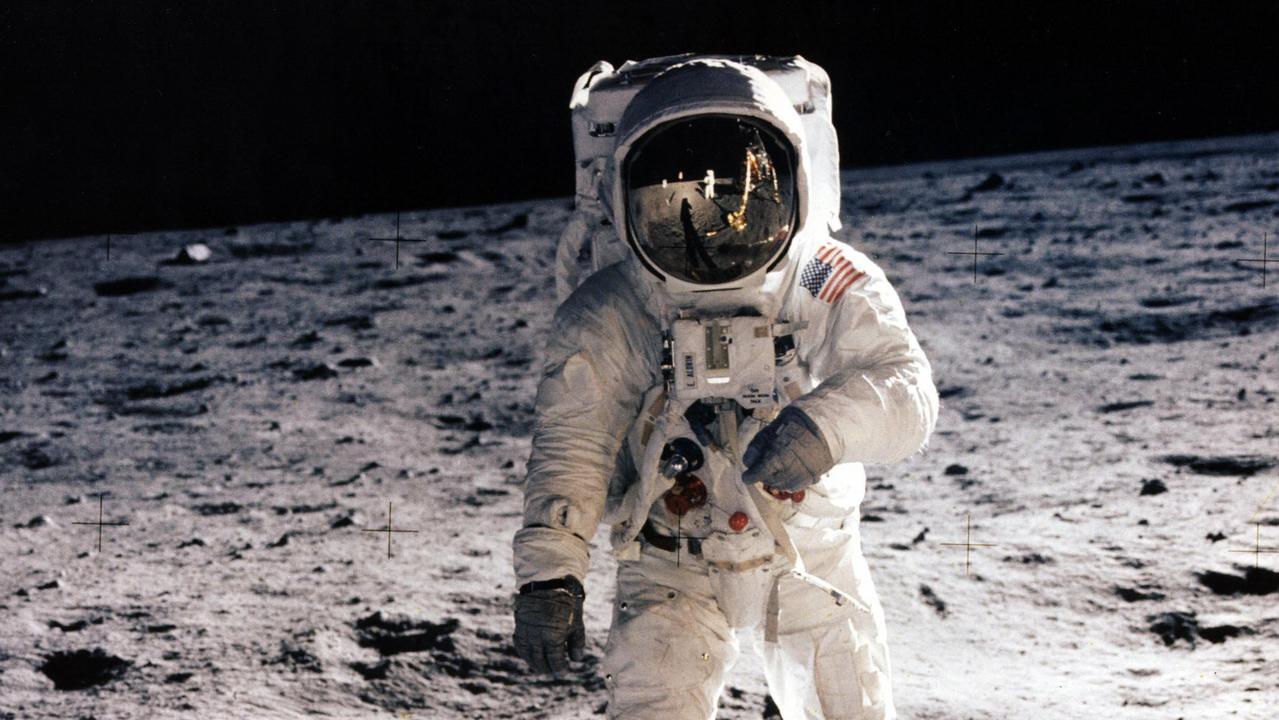

The hatch opened, and Neil Armstrong crawled out on his hands and knees, feet first, onto the platform.

As Mike Linney in our telemetry area watched the biomedical data coming in, he could see Armstrong’s heart rate racing at 112 beats per minute (it was normally in the 60s).

Armstrong climbed down onto the top rung of the ladder and released the black-and-white TV camera shutter.

Suddenly the flickering greyness on the TV monitors at Honeysuckle Creek gave way to a fuzzy black-and-white scene of a ladder and handrail — upside down!

A few seconds later, Ed von Renourard, the technical who operated the Honeysuckle Creek video-scan converter, realised what had happened and flicked the switch to put the picture right-way up.

Goldstone Tracking Station in California was also receiving the TV signal, but their picture was too fuzzy to make out. Houston immediately switched over to Honeysuckle Creek’s picture.

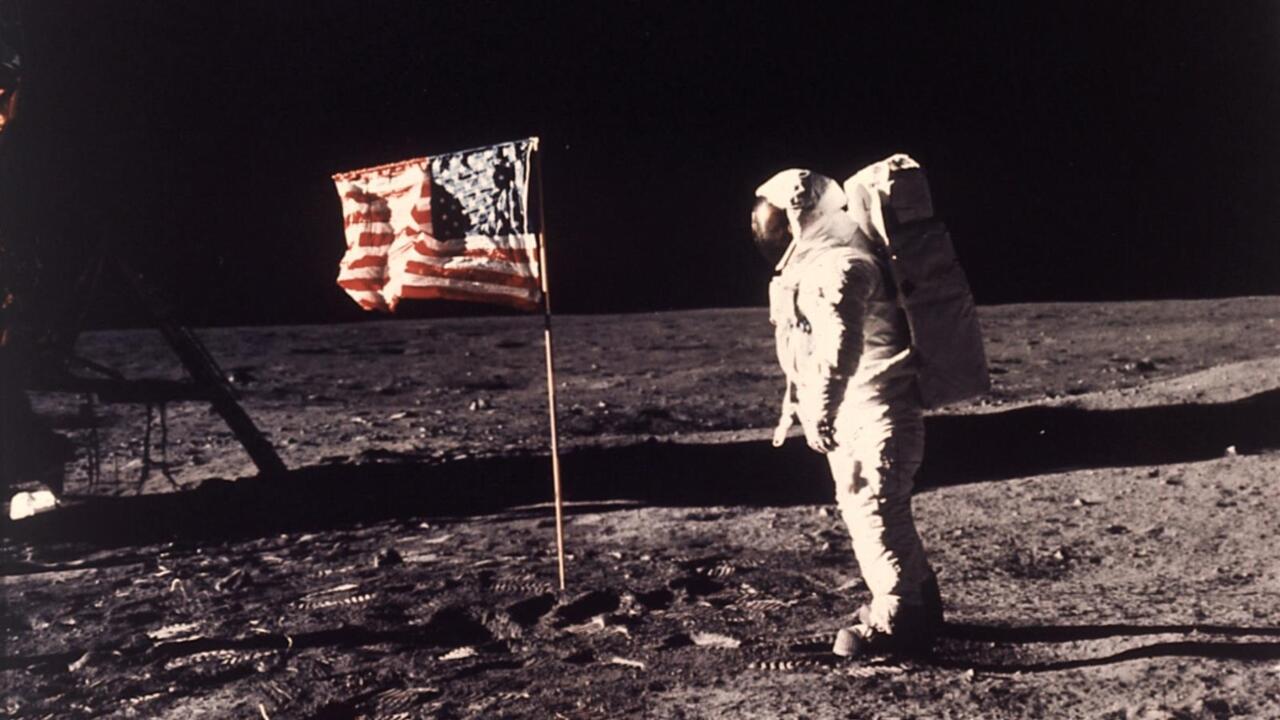

Neil Armstrong climbed slowly down the ladder and said: ‘I’m at the foot of the ladder. The lunar lander’s footpads are only depressed in the surface about one or two inches, although the surface appears to be very, very fine grained, as you get close to it. It’s almost like a powder.’

Then he stopped at the last rung of the ladder, stretched and placed his feet onto the top of the footpad, and finally stepped off the ladder into the dust.

He stood there for a moment, testing the soil with the tip of his boot.

He said: “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind”.

This was an edited extract from To the Moon and Back, by Bryan Sullivan and Jackie French, published by HarperCollins Children’s Books Australia, $16.99. Available now from all good bookshops and online.)

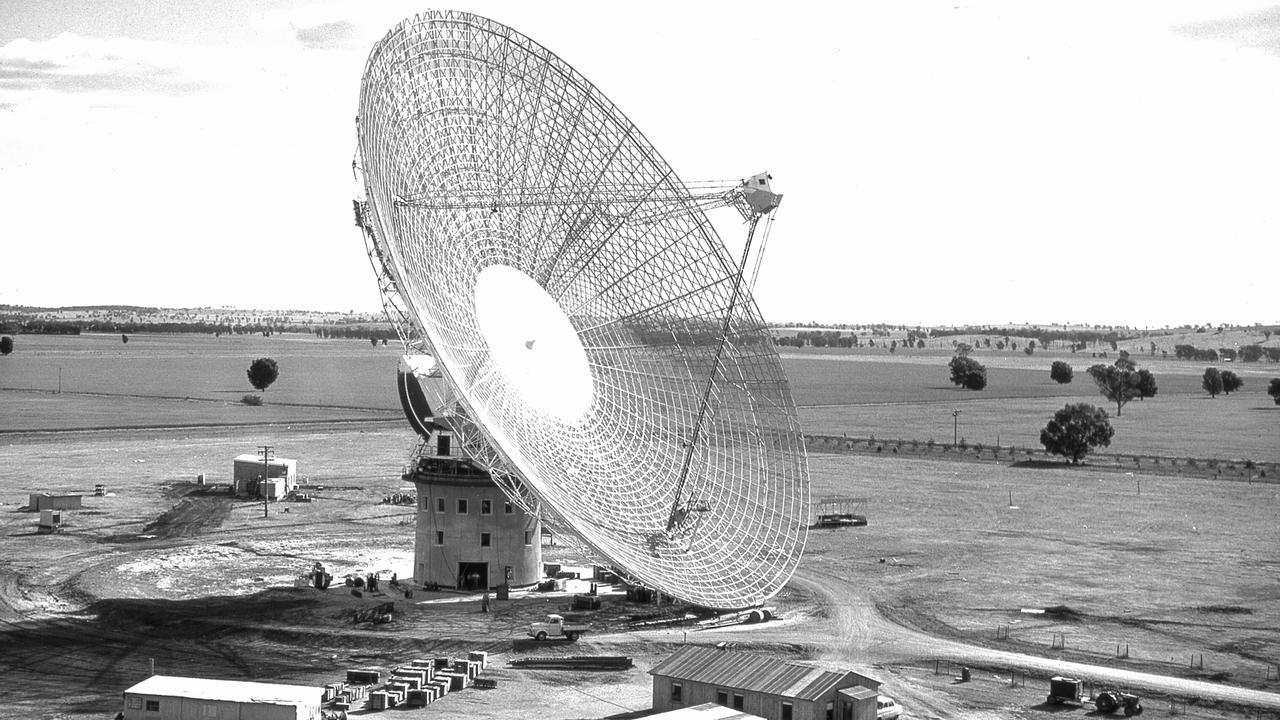

PARKES TELESCOPE

Honeysuckle Creek transmitted the first eight-and-a-half minutes of the moon landing before NASA decided Parkes’ feed from Australia was better quality and began transmitting it instead.

But not everything had been going to plan at Parkes either.

While the dish was fully tipped over waiting for the moon to rise, the Parkes telescope was hit by 110km/h gusts of wind, causing the control room to shudder. The telescope was slammed back against its zenith axis gears*, a dangerous situation for its structure.

Fortunately, the winds died down and the astronauts on the moon activated the TV camera just as the moon rose into the telescope’s field of view.

The Parkes radio telescope began tracking one of the greatest walks in history for the rest of the world to see.

The Parkes telescope followed every move of Armstrong and Aldrin for hours as they explored the lunar surface.

From inside the observatory, staff stared at a tiny green TV screen and could not quite believe it.

David Cooke, 87, was a receiver engineer on the day as the first images crackled to life. Even now, Mr Cooke said it was still hard to articulate* what it was like to have played a role in history.

A series of photos taken on the day, show him among several others standing in front of a monitor in amazement.

“I saw the picture of Armstrong coming down the ladder and putting his feet on the moon on that little green TV screen,” Mr Cooke said.

“After it was all over I went outside and the Moon was still there above us, of course.

“I was quite amazed to think, well, there were men up there and we had been a part of helping them get there.”

Following the mission the NASA Administrator, Thomas O. Paine, sent the following message of commendation* to the Australian Minister for Education and Science, Mr Malcolm Fraser: ‘I wish to express my sincere appreciation to you and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) for making available the Parkes facility during the Apollo 11 mission. Its participation, and spectacular performance, provided the entire world with a chance to experience, with astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin, this historic event’.

In 2000, the story of the Parkes telescope’s role in the moon landing was the subject of a fun Australian movie called The Dish.

A SCHOOLBOY’S RECOLLECTION

Jon Anderson is now an award-winning sports journalist with the Herald Sun newspaper in Melbourne, but in July 1969, he was a 12-year-old schoolboy at Wangaratta High School in Victoria.

Like tens of thousands of other schoolchildren across Australia, he had the honour of watching the moon landing live on TV while at school.

Here is what he remembers 50 years on:

“The television was specifically brought into our room by mathematics teacher Mrs May Osmotherley, the perfect teacher that every young student requires at some stage of their education.

Mrs Osmotherley had told us that two men were going to try and land on the moon, something I had seen in the sky often enough from our farm at Thoona, a hamlet 20 minutes from Wangaratta High School.

And it was in our Year 8 maths class that we sat down in the early afternoon of Monday, July 21, to watch a man named Armstrong walk upon the moon (it was July 20 in US time).

For 12-year-old me, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon didn’t carry the same importance as Geelong having two days earlier blowing a 22-point last quarter lead in the Victorian Football League to lose to St Kilda at Kardinia Park, despite forward Doug Wade kicking eight goals.

But then Armstrong appeared in this really cool fancy dress after getting out of a weird-looking contraption that Mrs Osmotherley said was a lunar module named Eagle.

I said to my mate Noel Porter the Eagle was even better than Dr Who’s time machine the Tardis, which masqueraded as a blue British police box.

But unlike Dr Who and his enemies the Daleks, this was the real deal as Armstrong and Aldrin seemed to bounce on the moon’s surface.

The coverage was in black and white and very grainy, but hey, they were a few miles away (252,088 miles to be exact) so far be it for we 12 year-olds to be critical.

Armstrong even spoke after he first set foot on the moon, declaring “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”.

Then he started digging the moon’s powdery surface, just like we had been doing six months earlier on the back beach at Point Lonsdale in Victoria.

Mrs Osmotherley said Armstrong’s words would become really famous, and then asked us all which other famous words we knew.

When my turn came I went with “I shook up the world”, which was what boxer Muhammad Ali had screamed five years earlier when he won the world heavyweight championship by stopping the champion Sonny Liston.

Mrs Osmotherley looked at me and sighed, before we went back to our writing, reading and arithmetic.”

GLOSSARY

- broadcasting: transmission of programs or information by radio or television

- receiver: a piece of radio or television apparatus that detects broadcast signals and converts them into visible or audible form

- technician: someone who looks after technical equipment

- Roger: a word to indicate your message has been received

- teleprinters: a device for sending messages

- interface: a device or program enabling a user to communicate with a computer

- status: the condition something is in

- data: facts and statistics collected for reference or analysis

- complexity: problem

- console: keyboard

- smug: too pleased with yourself

- frantically: in an upset way because of fear or anxiety

- essential: important

- zenith axis gears: gears that help move the dish

- articulate: speaking clearly and well

- commendation: official praise

EXTRA READING

Part 8: The moon landing

Part 10: Conspiracy theories that the landing was a fake

QUICK QUIZ

- Where were the two telescopes in Australia that broadcast the moon landing?

- Which was the first to show the images to the world?

- What was wrong with the first fuzzy images from the moon?

- What weather event almost caused disaster for one telescope?

- What plan changed meaning the US didn’t get the first images?

LISTEN TO THIS STORY

to come

CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES

Refer to the accompanying 50th Anniversary of the Moon Landing classroom workbook with 25 activities. Can be purchased for $5 including GST at https://kidsnews.myshopify.com/products/moon-landing

HAVE YOUR SAY: Name any historic events you have watched on TV.

No one-word answers. Use full sentences to explain your thinking. No comments will show until approved by editors.